Tony Côme

“What the Everyday Promises”

The first meeting was at the studio in the north of Paris. On the way, as if to signal the end of our discussions, I pass a boy holding a chromatic circle with very uncertain tones and contours. The paint is still fresh. An ordinary art exercise, for the schoolboy. A potential collector’s item for the two artists. Gaelle Hippolyte opens the door for me. The glass room is huge, the music demanding, the work spread out on the floor. Lina Hentgen, who has just returned from an expedition to Greece, is unpacking some kourabiedes.

Hippolyte Hentgen We needed a partner to organise our work, which is a real mess, in a book. We should rather say that it conjures up an abundant universe.

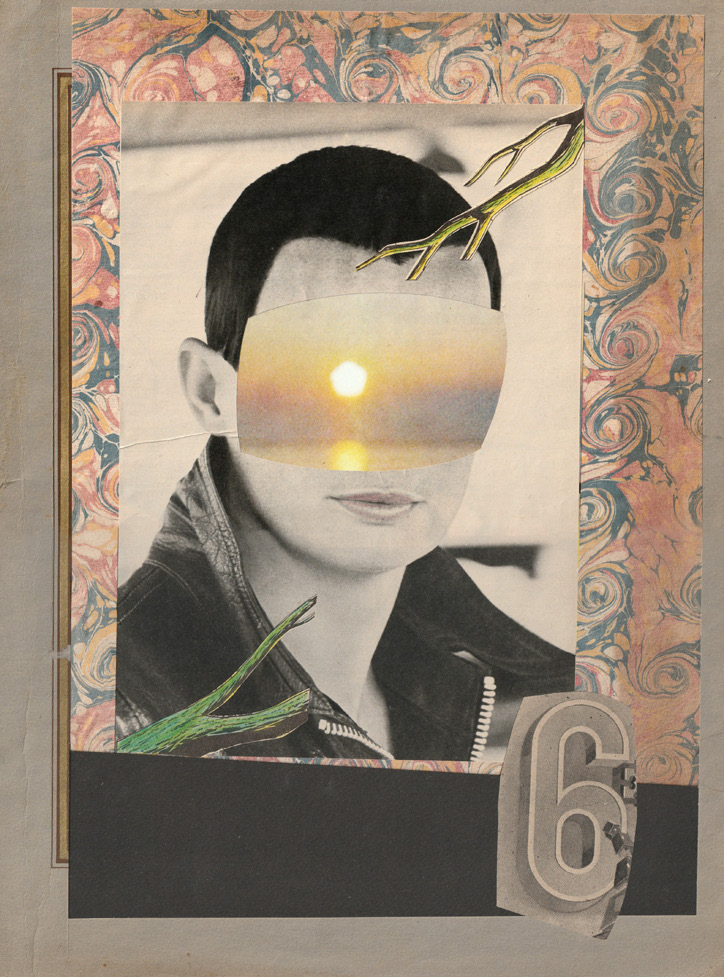

We called it Imagier, a title that came naturally. The imagier is the artist who makes images, but also the educational object that thematically crosses this whole. We’re also thinking of Alfred Jarry and Remy de Gourmont’s Ymagier, a magazine that we adore. It dates from the end of the 19th century. It was born out of their interest in popular imagery, and it was a mixture of explosion. Borrowing from documents and iconographic sources, although always in the same vein, fits into our work more directly, without being subject to a hierarchical relationship that seemed a little systematic and ultimately prevented us from looking carefully at our different models and their qualities and subtleties.

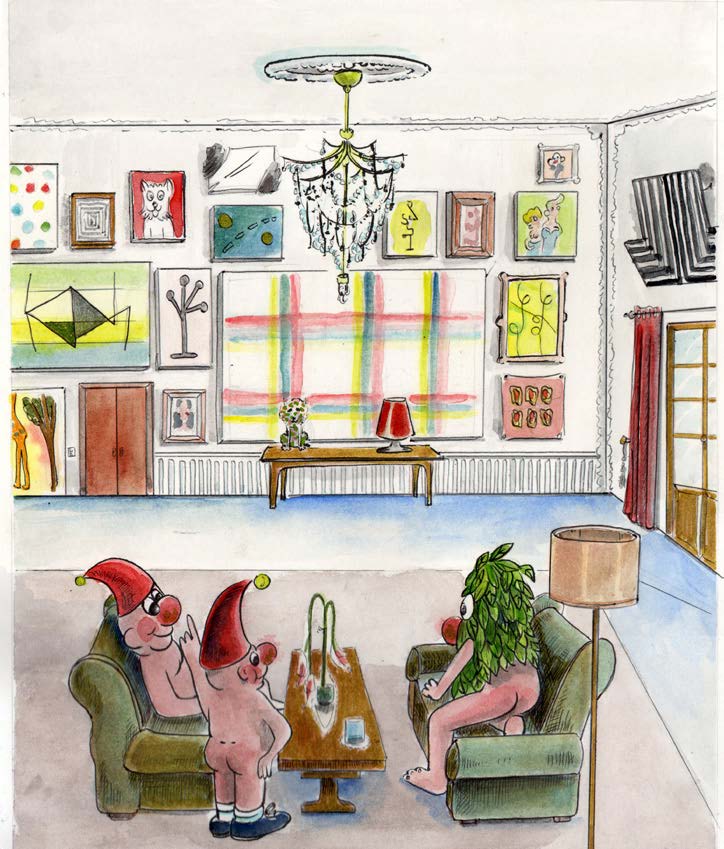

For us, this collection of images remains drawing in a way. Even when we paint, the imagery or the subject lovingly embraces the drawing. With this book, we’d like to take a closer look at the highly heteroclite content we manipulate, which is strongly linked to popular culture and the collective imagination..

Tony Côme In your work, you so often use the hand, so many hands, very literally: a hand borrowed from an actress, a hand copied from a comic strip, a hand cut out from an advertisement, Mickey Mouse hands, mittens, gloves, etc. It’s surely the most recurrent motif in your work. This is surely the most recurrent motif in your work. Is it also a symbolic way of showing that you don’t go it alone, of breaking with the romantic image of the isolated artist?

Hippolyte Hentgen The repetition of motifs, of clichés, suggested by history, is the subject that occupies us and we are trying to explore the different stylistic possibilities of these commonplaces. Giallo, genre films and experimental cinema1 (which we are looking at closely) embrace these issues and offer interesting readings between modernism and postmodernism.

For the hand motif, we’re also thinking of Bresson’s Pickpocket, which made a big impression on us and to which we return regularly. There are also certain similarities with Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Hitchcock’s The Rope. This is the cinema of the hand, of tactility, of fragmentation, and we find ourselves in a world where everything is given in pieces. These fragments show that the issues of representation, the idea of novelty and the place of the author are not simple today.

Drawing around your hand is one of the first drawings that each of us made as children. It’s when we learn about our self-image, when we measure the impact of the trace, the imprint, the sign. It’s a way of saying ‘I was here’, and from Lascaux to the present day, this sign remains moving.

Experimenting with form in the studio is at the heart of our practice, and the daily pleasure we derive from working largely with our hands. The hand is precision, it’s the multifunctional tool, whose varied geography (the palm, the thumb, etc.) serves to convey our intentions and affects.

Passing from hand to hand signals our interest in the collective, in the game; it’s a relay race, which also addresses the viewer and indicates a possible path. This recurring sign allows us to emphasise the fragments and give autonomy to the subjects and objects sketched out.

In our exhibition The Invisible Bikini at the MAMAC in 2019, the hand was the central figure. The motif was deployed in the form of animated sculptures laid out on the floor and surrounded by a series of wire animations - a corps de ballet. For this series of stop-motion animations, we used the choreography from Trisha Brown’s Water Motor2.

In 1966, the filmmaker Yvonne Rainer made a film in her hospital room: a minimal ballet of folded fingers that maintains tension in the hand. We wanted to adapt this minimal five-finger ballet to the glued hand…